Last month, my friend Coby Lefkowitz (@cobylefko) published a widely read piece entitled “Why small developers are getting squeezed out of the housing market”. Both technical and even manifesto-ish, it underscored many of the same points I have been saying: localism is dying, there is an unholy NIMBY alliance that is underwriting crony capitalism, the zoning and financing system is broken, and our cities are threatened by all of it.

I met Coby at last year's I'on Dialogue, where he was one of a half-dozen millennial developers studying Charleston's old and new successes in the hope of finding precedent for their own fledgling careers.

Coby is a talented writer, and I have admired his optimism on social media. Juxtaposed with my own sometimes Eeyore-meets-Lewis-Black tone, he reminds us all that cities are incredible places where extraordinary things happen. His positivity is contagious, and it resonates through his prose.

Coby has skills and experiences that I do not have—an architecture degree, institutional investment experience, and a large readership—all of which make him a novel read. Most importantly, he is a fledgling young developer. By throwing himself out of the stands and into the arena, he makes his views and viewpoints valid and essential.

Here are my thoughts on his.

1 URBANISM IS WINNING

Coby begins by underscoring that Urbanism is winning. Rather than the constant whining that has engulfed public discourse this century, urbanism offers real solutions for affordability, dynamics, and resiliency. Through grassroots activism, Urbanists are healing cities through reforms such as the abolition of single-family zoning, form-based codes, parking reform, and single-stair reform.

Still, there are no silver bullets; citybuilding is a journey, not a destination. New York City is forever. It has no final boss. There is no utopia to be obtained. Only a more perfect union.

One area where Coby stands out is finance. His recent conversation with Geoff Graham on The Yeoman Podcast explained how changes in finance and building codes over the last 20-30 years have completely formed the built environment we know and hate today.

Specifically, credit markets and tax policy have tilted the playing field in favor of institutional interests at the expense of local practice (and thus against local architecture, local flavor, and local culture). Zoning regimes—cookie cutter, boilerplate, and placeless—have only worsened it. Combined, these organizations form a modern machine, a Private Public Pariah (Geoff Graham identifies the culprit as Dodd-Frank, but that's a story for another day).

The squashing of local practice undermines everything. Institutional interests are pressured into the monolith. The Machine doesn't do scrappy coffee shops, punk clubs, James Beard restaurants, or small retail.

The Machine can only do big, and big is almost exclusively dumb.

Between punitive finance and punitive zoning, small developers struggle to get loans, the industry's lifeblood. It’s becoming harder and harder to do even one project. Deprived of access, no one new can enter.

The situation reminds me of what is known as “The SAG Card Paradox.” SAG stands for Screen Actors Guild, which requires its members to carry a membership card. Functionally, this means that you need a SAG card to act in movies. How do you get a card, you ask? The only way to get one is to act in a movie. Well how is anyone supposed to play that game?

Relieved of perpetual competition, the industry consolidates and becomes more and more hostile to outsiders over time, particularly upstarts and independents.

One might call this century of real estate development "The Great Consolidation". Coby writes:

"These imperatives privilege a concentration of the most well-capitalized firms who have done the most projects before. In 2022, nearly 25% of all multifamily units started in the country (more than 132,000) were commenced by just 25 developers. That's a strikingly high percentage in a country of more than 60,000 developers."

What’s fueling the centralization of power? One thing is the efficiency of size. It's far preferable to arrange debt financing on $100 million rather than $1 million. The same amount of work, coupled with a much larger fee.

This reminds me of my (more incremental scale) conversation with Canadian developer Sean McAdam of Land Lab: "Sean, call me crazy, but I think it's easier to build ten houses than it is to build one." He said, "It's absolutely easier to build ten houses than it is to build one."

2 "With more big buildings, there are fewer small buildings."

We should care about the institutionalization of real estate. For Coby, this is, first and foremost, a qualitative concern:

"It's my belief that it's better for the health of a neighborhood if more buildings are constructed by the people who live within it, or at least in the area. Fewer local developers, the corollary follows, diminishes the health and character of a neighborhood."

Notably, NIMBYism attacks the local developer, not the corporate one. Why? Some of this is just straight sadism. The local developer is the devil-you-know. Jerry Smith of Smith Construction is here. He’s in your city. You can yell at him in person.

You can drag Jerry’s name through the mud on Nextdoor, and he'll hear about it at church. But the institutional developer? You can’t. He hires an engineer or lawyer for all the public touchpoints and has no local social circle available for the NIMBY to leverage. This reality further tilts the playing field away from localism.

3 LOCALISM FOSTERS PRIDE

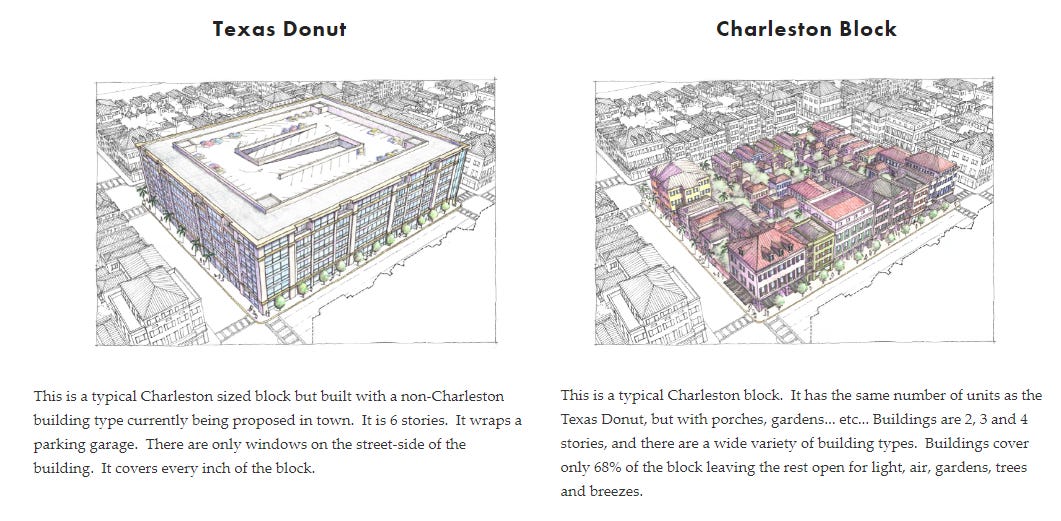

Survey your city, and you will find that only locals build with pride, while institutions do not (this is true across the country). "5-over-1s" are soulless buildings, the inorganic architectural equivalent of being dead on the inside. They are McMansionism on steroids. Texas Donuts proves Mitt Romney wrong—corporations are not "people too." They are machines, as Coby explains by detailing how these projects are financed.

These $50-100m apartment complexes are typically backed by insurance companies and pension funds. That luxury condo you hate? It's paying for some 75-year-old teacher's retirement. So that's good, but that teacher has no idea what this apartment is, how good it is, if it creates a place, fosters community, or adds any flavor to the city. They probably do not even know where the property is. And they do not care.

And that, Coby posits, is a big part of the problem.

"When you build in your own neighborhood, a pride imperative materializes. If you have to go by a project frequently, you want to feel good about the fruits of your labor."

The canary in the coal mine? I can show you the last ten big apartment buildings built in Downtown Durham in the last ten years; none are locally owned. Localism is on the retreat, and this matters.

4 ONLY THE SMALL LOCAL CAN DO SOCIAL GOOD

Small developers diverge from large ones when it comes to returns as well. They tend to be less motivated by squeezing every last dollar out of a project than creating somewhere they can be proud of. Institutional developers have to hit a specific rate of return to satisfy the needs of their Limited Partners, who are pensioners, insurance recipients, scholarship students, and sophisticated high-net-worth individuals, all with zero qualitative or moral motivations.

Coby starts a section with the phrase, "When you build in your own neighborhood, a pride imperative materializes." You see it, you touch it, you show it to your children. "Institutional developers rarely build in their backyards," and that matters.

Validating the thesis, I visited Charlotte for CNU 31 last year and noticed that The Queen City's multifamily projects look consistently better than the Triangles. Why? Charlotte is a banking town, and much of the equity for these projects is local. Even though the demographics and wealth of Charlotte and RDU are nearly identical, Charlotte is building better stuff. Why? Because it's local.

That Charlotte banker will talk with their kid someday about what they built. They want it to be decent, so they take the time to make it better. If that same investment is in some place they'll never go—Huntsville, Ft Collins, or Jupiter—they simply care less. As distance away from vested interest increases, qualitative factors decrease. Design is worse. Localism matters.

I know local property owners who rent at 50% market rate because they want to support someone who needs it. Another builder holds a duplex empty to host families undergoing traumatic treatment at Duke. Another group is planning to host cancer patients in medium-to-long-term care at Duke. All for free, and all local.

Institutional investors will never do this. Localism matters.

The most ambitious green projects—the LEED projects and the NetZero projects—are all local. The best affordable housing projects (real affordability via lower cost, not fake affordability via subsidy) are all local. The best co-housing communities, encouraging unprecedented levels of intentional community through design, are all local.

Small builders also continue the spirit of a local place, the spirit of historic preservation. I recently retweeted a great quote from Witold Rybczynski's book Charleston Fancy:

"The builders who create – and preserve – a city's everyday fabric are as important as the founders and city fathers, for it is CONTINUITY that is the key to effective city building."

His point is that institutional developers will never enhance localism. Definitionally, they subscribe to the one-world church of modernism, where the same off-the-shelf glass box or 5-over-1 apartment building works in Chicago, Charlotte, or Constantinople.

As it turns out, if you want Charleston to look like Charleston you need people from Charleston to keep it that way.

As Coby says, "We have institutionalized our communities and drained the charm and soul out of them."

5 CENTRALIZATION IS THE CURSE

Coby is extraordinarily knowledgeable about finance, which is perhaps the final frontier of reform (too few people are working in this space). He writes extensively on finance in this piece, which I will try to cover in another post later. The short summary of his thoughts is that the centralization of financial decision-making, a consolidation that resulted from the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, has benefited institutional interests at the expense of localism.

We need to switch it back, which is virtually impossible. That leaves the dwindling number of local developers left with bad and worse options.

I am on record with leaders in the Congress of New Urbanism and National Townbuilders stating that the movement has failed to produce its next generation of great developers, a “Townbuilding Farm Team”, so to speak. The lack of a bench is an existential threat to the urbanist movement and American cities.

Coby is right to identify the squeezing of the small developer as kind of a big deal.

When pressed to identify young urban development talent, I would put Coby on that list. Keep an eye on his work. Not only is he a great writer, he’s driven and trying to develop cities. Most of all, he is young. And when trying to reproduce and continue movements, that matters.