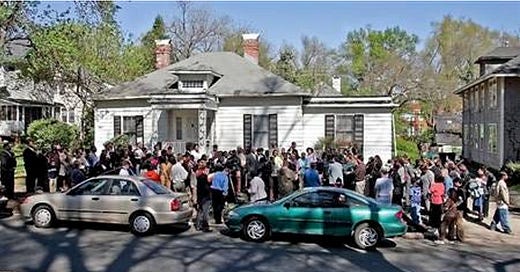

How it started:

How it’s going:

Well, this one is a doozy of a story. The story of what happened in the old home is well documented. Accusations. Community rage. 13 months of hell. Exonerations. Yada Yada.

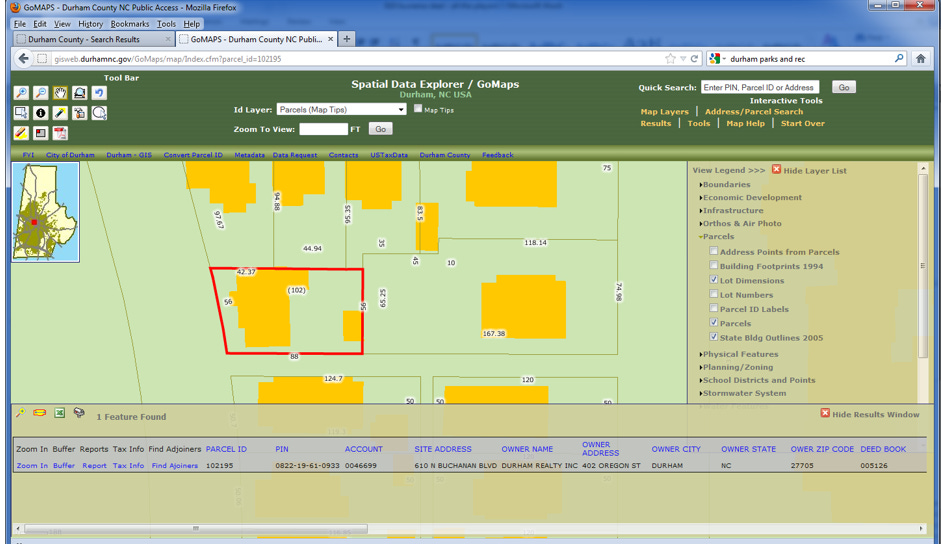

What was not widely published is that Duke University owned the house at the time of the alleged events. This was the result of a strange but creative deal to purchase 15 of Trinity Properties’ student rentals, mostly in an effort to reduce de facto fraternity partying on the campus wall and improve relations with surrounding neighbors. The intent and ultimate plan was to sell these houses back to the community, with a preference for faculty and staff to turn them into owner-occupied homes, making the problem disappear.

Then the lacrosse team hired a stripper, and that stripper had a few issues, and things descended from there.

After 13 months of Durham facing daily coverage in national news, Roy Cooper came out and told the world that we were done here. Mike Nifong was disbarred in disgrace, and a few years later, lawsuits were settled between the accused, Duke, and the city, including claims of violations of civil rights and due process.

You have never seen a house demolished more quickly. It came down, on July 12, 2010, more than four years after that night. The sun came up, they were demo-ing. By sundown, the lot was graded and covered with hay.

What was an effort to make good with the community quickly turned into the biggest of PR nightmares. Durham runs on optics more than reality, a truism present throughout the community’s throwing of the (rich, white, northern, etc.) lacrosse players under the bus.

Duke facilitating more owner-occupied housing and reducing nuisances in the neighborhoods were both valid goals. And those genuinely had nothing to do with the March 13, 2006 events. But college towns being college towns, they two were conflated in the community. No good deed goes unpunished, especially near a university.

Scott Selig, Director of Real Estate at Duke, approached me about building a home here.

Selig oversees massive real estate deals. Every lease signed by the university goes through his desk. 10-15 years ago, much of that was getting the Duke Chinese Kushan campus out of the ground, underwriting downtown Durham’s rebirth through letter-of-credit leases, and expanding the Duke Health System across the Triangle.

That’s to say, Scott doesn’t have time to build a one-off house at 610 N. Buchanan. Duke doesn’t really do residential, and this is just wrong-sized for the controlling entity. It’s too small.

It was massive for me.

Our practice at Trinity Design | Build had grown fast from the moment we opened our doors in 2003. And while we had done a few major projects (by our standards, not Duke’s), they were almost exclusively in the world of historic restoration. New construction was a different animal. In many ways, it is easier, but it is definitely new. And it was not what we were set up to do.

Selig asked that we bring him a proposal, which we did. And it was an odd one. Universities are odd housing partners. Money doesn’t really matter. Purpose does. I mean money does matter, but it’s not the prime mover. Selig could have just sold the land for top dollar. He didn’t want to do that.

Something better could be done here. Something better needed to be done here.

Our challenge was creating a mutually beneficial structure for all parties. That’s easy in the private world, where it is mostly about money exchanged for products and services. But in the non-profit world, there’s a narrative. Narratives are hard to price. It's impossible, really.

So here’s what we proposed.

It’d be $100,000 for the land; at the time, that was really expensive. It was the smallest lot in Trinity Park, and whatever would be built would have practically no backyard, a major red flag in desirable neighborhoods where people expect yards.

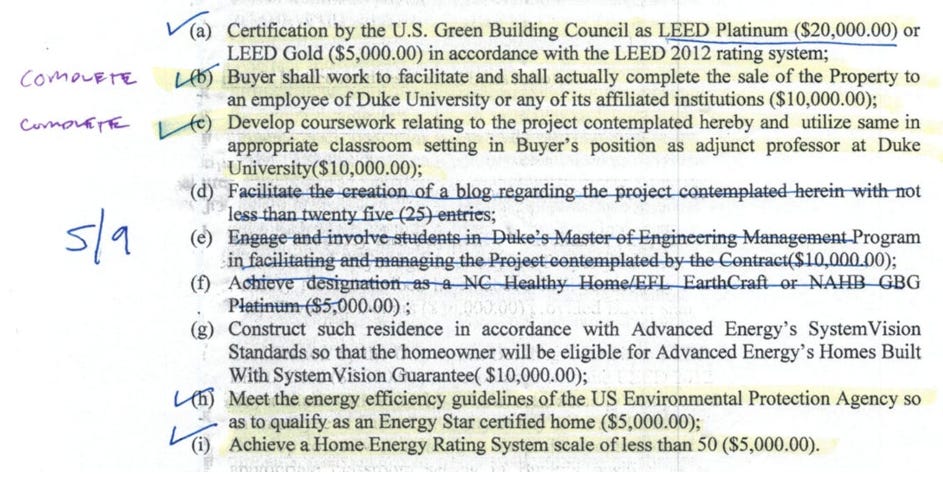

Then incentives were added for achieving each of the following goals, with a maximum incentive of $50,000.

Essentially, we had a pool of 9 incentives to choose from and could receive a maximum subsidy of $50,000 for accomplishing them. We ultimately received that maximum incentive by 1) achieving LEED Platinum, 2) selling to a Duke employee, 3) developing coursework around the project, 4) certifying Energy Star, and 5) achieving a HERS rating of less than 50.

We hit ‘HERS Zero’, a net-zero energy home.

And we believe it was Durham’s first Net-Zero Energy Home.

More on that, and this crazy story, in part 2.

This is a duplicate copy of the article to facilitate email deliver to subscribers.