What’s Next for Jane Jacobs' Sidewalk Ballet?

Despite widespread acceptance of her beliefs, Jane Jacobs failed to create the world she coveted.

Washington Square Park, 1961. It was here that Jane Jacobs came to brawl with Robert Moses, the larger-than-life planner of housing and transportation for a rapidly modernizing postwar New York City, and effectively ended the era of authoritarian planning.

Their specific conflict was over two of Moses’s many master plans: The first proposed to raze sections of Jacobs’s chaotic, vibrant, and old Greenwich Village to construct Corbusian “towers in the park,” a Bauhaus-inspired modernist style in vogue with the planners of the time. The second plan promised construction of the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX), intended to connect the West Side of Manhattan to Brooklyn, also by taking out entire blocks of historic Village fabric.

Washington Square Village was ultimately built under the rationale of “slum clearance” and displaced thousands of small businesses. But for Moses, the victory would prove pyrrhic. Thanks to Jacobs’s relentless pen and grassroots organizing, she ultimately stopped the freeway and saved the park. The scale of this fight established long-overdue boundaries for Moses’s unprecedented, ever-expanding powers. As a result, she forced a major turning point in the fields of urbanism and urban planning.

That fight served as an inflection point because Moses’s power grew to where he was no longer accountable to anyone—a critical characteristic of the leviathan-like scale he, and only he, operated at. The planning movement that he led had turned into the most pervasive and damaging tentacle of the early twentieth century’s Progressive Movement was effectively ended by Jacobs’s work. What came next is of mixed consequence.

“People make cities, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”

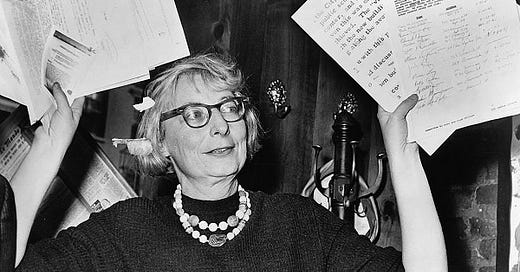

As Alexiou’s 2006 biography reminds us, Jane Jacobs was known as a contrarian figure, “a militant dame” and “an amateur who had no right to interfere with established discipline,” at least by her adversaries. And with these opponents, she pulled no punches. An outsider with no formal training or expensive credentialing, she operated in a field exclusively reserved for expert white men, whom she described as pseudoscientists. For such troubles, she was labeled a “housewife.” Few industries were as firmly rooted in patronizing patriarchy as post-Euclidean planning. Jacobs changed all that.

Jacobs’s work reconsidered cities in a new light. Her greatest innovation shifted the conversation around planning away from the order and efficiency of buildings and refocused it on the people who utilized cities to their delight. She gained a following by championing these people, a mission evident in her most quoted line from her seminal work, The Death and Life of American Cities: “People make cities, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”'

One of the greatest lessons from Jacobs is that only someone from outside the industry is capable of smacking a hornet’s nest in a way that brings about transformational change. Her writings rejected the Bauhaus rationalists and Garden City orthodoxies that advocated for orderly single-use zonings and technocratically forced suburbanization. In contrast, she grounded her arguments in the theories of F.A. Hayek, Adam Ferguson, and Adam Smith. She went on to inspire some of the most influential modern urbanist thinkers active today, including Andrés Duany, Chuck Mahron, and Nassim Nicholas Taleb (who describes Jacobs’s work as “antifragile to cities”).

Death and Life became the most famous book on urban planning. It is fundamentally about the natural origins and benefits of “the spontaneous order.” Written a third of a century after Euclid normalized centralized planning, Death and Life rejected that precedent, arguing that throughout human history, cities had been built on spontaneity, with millions of decisions made every day, beautifully and efficiently, with no maker.

This order created uncoordinated systems that worked, without staff, as if by magic. Such was Jacobs’s “Sidewalk Ballet.” With density, she argued, came “eyes on the street,” a community-based security system that required neither barbed wire nor an extensive police presence. With wide sidewalks comes trusted interactions, even with strangers—a quality peculiar to occupants of Southern McMansions situated on half-acre lots.

Cities, with a combination of old and new buildings (their mutual existence was a quality of growth rather than development, a distinction over which Jacobs was stubborn), maintained space for both big, established companies and bootstrap start-ups. Each benefited from the other’s presence as they grew the economy and improved quality of life. Such quality was the product of one solution—a non-solution, really—the spontaneous order.

Jacobs’s work is now required reading in planning programs, a tribute to her transformation of the profession. Remarkable for someone unequivocally seen as an enemy 60 years ago. But despite its homage to Jacobs’s sociological observations, the professional practice of city planning is still dominated by authority: grand plans, centrally drawn, now ostensibly with civic participation, with structural barricades erected at every level to fight even the smallest deviations from organic change.

Consider the obtuseness plaguing America’s most progressive cities. Planning remains dogmatic, ideologically resistant to markets, and scornful of the flexibility and responsiveness inherent within them. Here, Jacobs failed. Planners today broadly want cities to be more like Greenwich Village, and so they codify them to be so. This is a contemptuous misreading of Jacobs, who was for mandating little and once advocated for the elimination of zoning (which she saw as anti-urban) in its entirety.

In his 2020 article from Reason, Patrick Tuohey identified modern planning as using Jacobs under a false flag, arguing, “Today’s planners may have learned the dangers of subsidized suburban development, but they’re still addicted to top-down development schemes.” Further, and partially because of the profession’s debacle at Washington Square, planning has abdicated significant power (particularly veto power) to unelected, unaccountable boards, creating a new set of problems.

As urbanist writer Nolan Gray has argued via Strong Towns, “While Hayekian ideas have largely driven centralized economic planning into the dustbin of history, I suspect the Jacobsian urban revolution has only just begun.”

It is this revolution that this column shall consider. Jacobs stood for localism, humanism, and choice. She rejected feigned expertise, authority, and hubris. Today, as choice wanes and authority rises, her work is more important than ever. Her advocacy is the moral compass of the many latter-day urbanists who are reversing the exodus away from cities. In this spirit, we owe Jane Jacobs a debt of gratitude. This column exists in her image.

This piece was originally printed in Issue 1 of Southern Urbanism Quarterly.

Aaron Lubeck, Jacobs Columnist at Southern Urbanism, is a new urban builder and designer in Durham, North Carolina. He is the author of Green Restorations: Sustainable Building in Historic Homes, and a children’s book on Accessory Dwellings entitled Heather Has Two Dwellings, and host of the National Townbuilder Association’s “Townbuilder’s Podcast”. Follow Aaron at @aaron_lubeck