Teacher Housing On School Property?

NC Rep. Vernetta Alston just filed an interesting bill that aims to use public lands in Durham for affordable rental housing.

Last month, Durham's House Representative Vernetta Alston filed HB 1067, an interesting bill named Employee Housing in Durham County. It matches a Senate Bill (SB 905) filed by Durham County Senator Mike Woodard.

The bill authorizes two subject beneficiaries, Durham County and the Durham County School Board of Education (Durham Public Schools, or DPS), to provide affordable rental housing for teachers, police, first responders, and other county employees.

It allows these two entities to enter into a partnership, land trust, or joint venture to provide housing on the property now owned by the public school or the county.

Section 3 allows the beneficiaries to contract with any person, partnership, corporation, or business entity to finance, construct, and manage such affordable housing.

75% of the homes must be reserved for teachers.

"Under current state law, school boards are prohibited from doing anything not related to education on their property. This bill would allow DPS to develop housing on its property."

HB 1067 is remarkable to me for a few reasons: 1) Alston now has an established history of filing housing bills in the legislature, and 2) it is odd that a statewide bill would be limited to one county.

Sen. Woodard helped clarify via email: "Under current state law, school boards are prohibited from doing anything not related to education on their property. This bill would allow DPS to develop housing on its property."

But couldn't school systems subdivide their oversized parcels and shave off enough land for an affordable cottage community? According to Woodard: "School systems do not have the authority to do this."

Thus, the bills.

TALK OF TEACHER WORKFORCE HOUSING IS NOT NEW

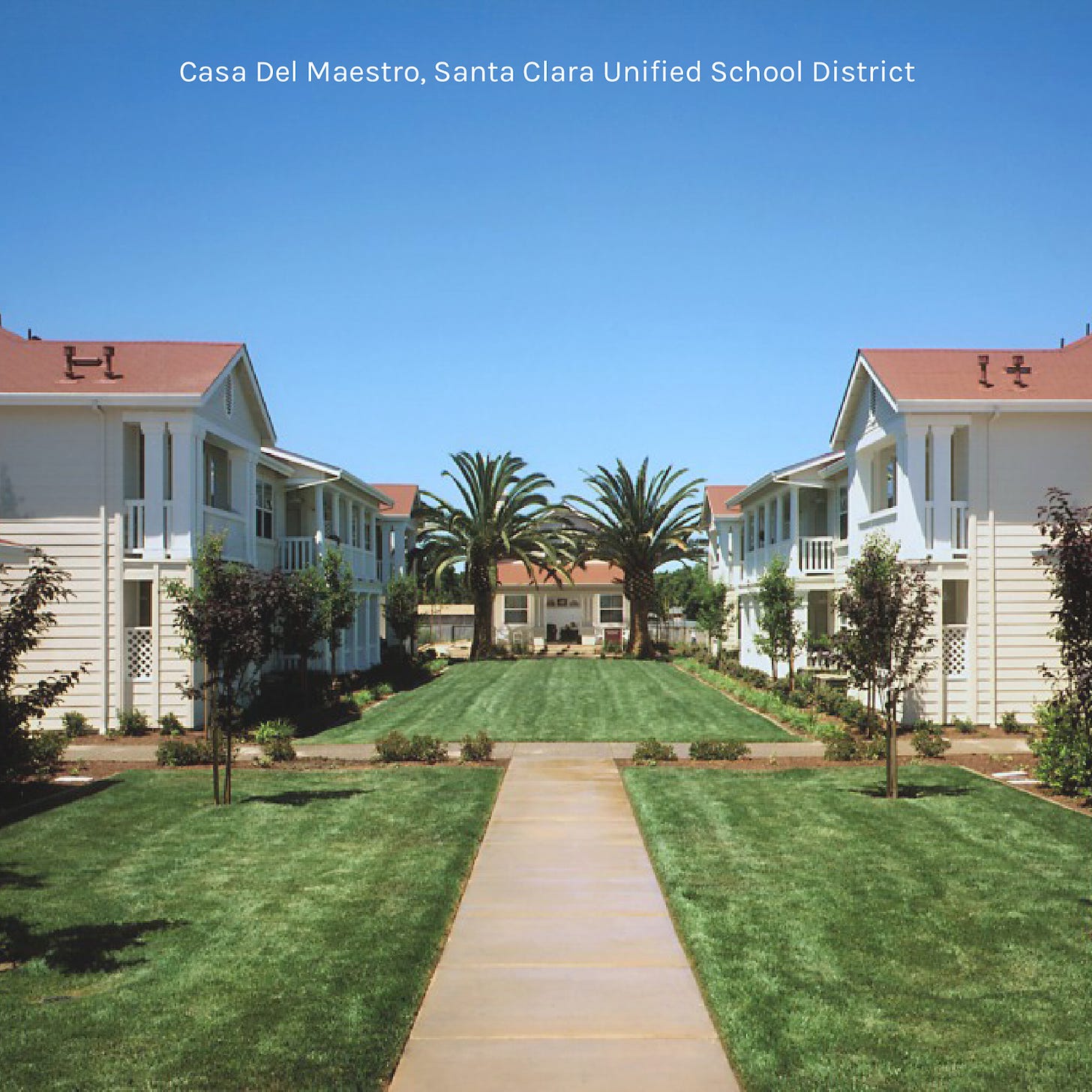

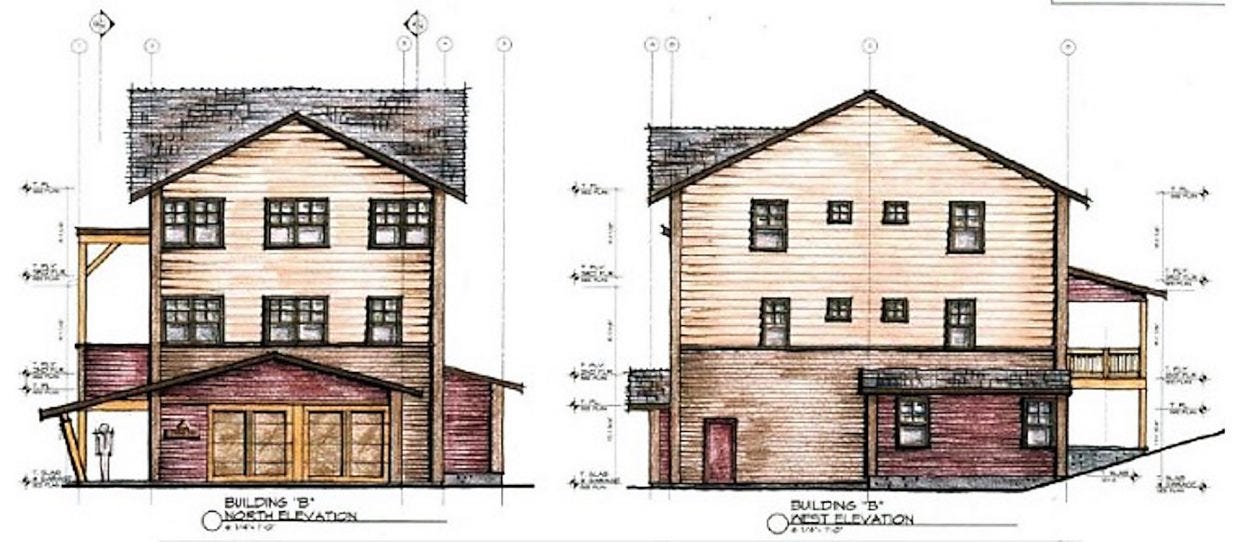

Building intentional community housing on school property isn't a new concept.

Liz Schlemmer at WUNC reports that a new foundation called Partners for Bertie County Public Schools will open a 24-unit apartment complex in Windsor designed to house teachers.

UNC's School of Government penned a piece about the State Employees Credit Union partnering with school districts to construct affordable housing for teachers. Schools have "donated surplus land for development, local governments have worked closely to ensure the property infrastructure is in place, and the SECU finances the construction with an interest-free loan."

A WRAL piece by Sarah Krueger indicates that housing for teachers on school property idea dates back to at least 2017.

Still, teacher housing on school property appears to be more smoke than fire. Despite lots of talk about it, there are very few examples of completed projects to cite. The few out there are stock garden apartments, often for teachers but not on school property, and radiate that affordable housing patina of impermanence where they look marginally functional but uninspiring.

CRITICS

There are fair critiques of the intentional teacher-housing model.

First, the most uncomplicated and straightforward objection is that governments don't have a good recent development track record, and it would be better and cheaper to let the private market fill these voids. More than anything, regulatory reform is required to make smaller, more affordable homes that teachers (and others) demand more widely available. Governments should start there.

John Locke Foundation argues, "Instead of turning school districts into landlords, better options might be to increase teacher salaries and improve zoning and regulations to bring about more housing options"

Second, it's fair to assert that teachers deserve to be their own favored class. Many North Carolina communities are struggling to recruit and retain teachers, and in this sense, teachers might be considered a critical job that deserves special favor.

However, filtering by employment type and not income excludes other equally deserving but less identifiable classes, such as bartenders, janitors, yard maintenance workers, and even other public school employees. I only point out that the same can be said of many other roles, such as police and perhaps a dozen other workers. Are we expected to count on our cities, which are historically bad at developing anything, to create intentional housing for each and every class?

INTENTIONAL COMMUNITY IS HARD WORK

A substantial part of my work focuses on the design of intentional communities. I believe that identity practice is a private matter, and when it shifts to the public domain, it becomes somewhere between messy and immoral. Governments are designed to be fundamentally neutral and, as such, should not be in a position of discrimination. Functionally, the way these class-based affordable housing programs are designed will inherently discriminate against otherwise income-qualified people specifically because they are not teachers. That goes against the principles of equal protection and equality in the eyes of the law.

Now, if ten teachers sought to organize to build their own community and restrict it to teachers, that would work. And it would be great. And it should be encouraged and supported in every way.

Freedom to associate means freedom from association, too. But that's a private practice and employment type is not a protected class under the Fair Housing Act. In other words, teachers can legally build a cottage court, and the deed-restrict occupancy to teachers. 100% legal.

But it's messy when a government performs the same task. It’s messy when a government intentionally excludes. I have concerns about the legality and exclusion of a government from taking those same steps.

HOW TO MAKE IT WORK

With the above concerns noted, I wholeheartedly support building low-cost housing and aggressively pursuing high-quality developments on public land. Let's talk about what needs to happen to ensure it works:

1) Will the affordable housing have to comply with the city's byzantine and practically unworkable rules? If it does, it will delay housing, making it significantly more costly and (critically and often ignored) more scarce. A simple alternative would be to deed restrict teacher housing in perpetuity, cap the rents at a fixed value, and skip all the unproductive compliance nonsense.

Why restrict the units to rentals? Do Durham's teachers, police officers, and first responders not want to own their homes?

2) Why restrict the units to rentals? Do Durham's teachers, police officers, and first responders not want to own their homes? There may be many reasons for this: titling may not allow the schools to sell land; a relevant power broker in this project may believe that rentals are more important; DPS is famously bureaucratic and grossly over budget with development; to expect it to execute a complex project with multiple variables would be hopeful at best. While the current all-rental plan limits choices and might not serve many deserving teachers, restricting the project exclusively to rental OR for sale makes operational sense.

3) Can we really count on the public schools to build public housing? I'd be concerned about an execution problem here. Schools don't really develop, and there's no reason to expect they'd be any good at it. There is no risk motive, no reward motive, and few (if anyone) on staff with experience building things, let alone housing (there is a Building Services Division, headed by an architect, that appears to outsource all construction activity to third parties and act mostly as a funding conduit).

With everything local governments build being 1) subjected to politics and 2) reliant on third parties for execution, teacher housing has all the ingredients for yet another Durham project that fails to execute and probably can't even get past the engagement phase. At this point, we should openly acknowledge these past failures in the hope of not repeating them.

The first step is admitting you have a problem.

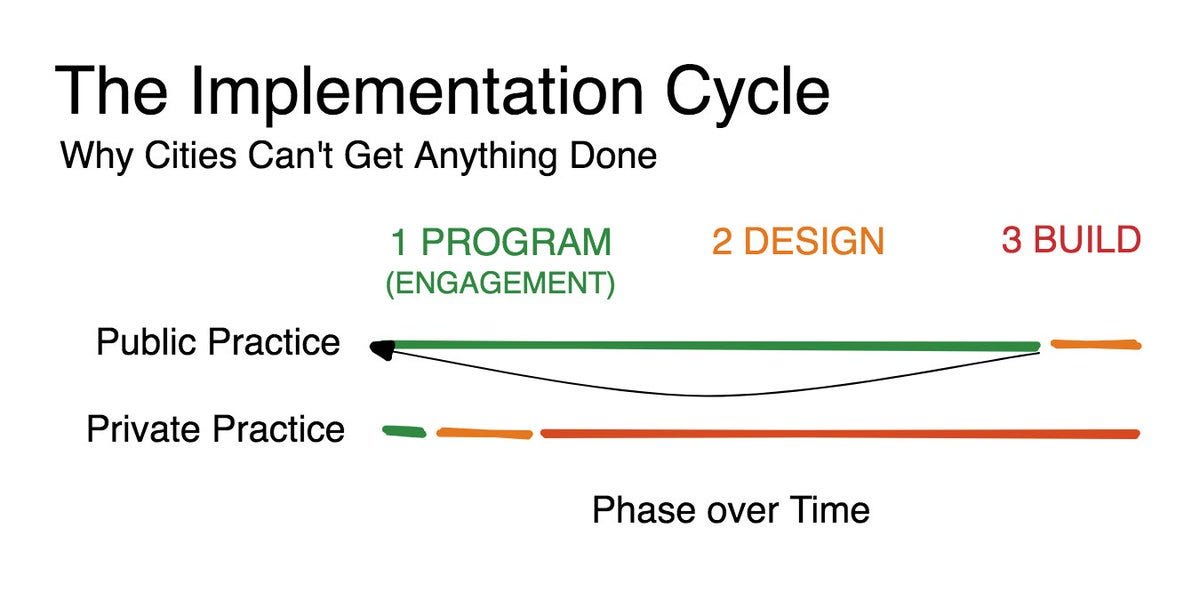

Durham suffers from what a county manager once labeled "Progressive Paralysis," the inability of blue cities to get things done.

The reason is what I call “The Participatory Paradox," which states that the more engagement there is, the less productive a process becomes.

Here, in the case of proposed housing on public lands, we should all expect Durham to host public teacher housing events (for maybe a year?), none of which will have anything to do with site design (or architecture, or amenity, or development, or ongoing management). Many will turn into complaint sessions. Most will be unproductive, and the longer it goes on, the less it will have anything to do with the primary beneficiaries of the proposed housing.

The diagram above explains the problem. In any development project, there are three phases: Program, Design, and Build. Public entities cannot execute because they are perpetually investing in the Program phase and, worse, cannot get out of it.

Often, cities can take years to run an engagement cycle, and at the end of it, politics have changed, and new people want to be heard, so the simplest solution is to just start it over again. And again. I call it “Groundhog Day Planning”.

There are many reasons for this execution problem, all worthy of unpacking later, but it appears self-perpetuating. As housing gets worse, we feel the need to talk about it more. As we spend more and more (and more) time talking about it, we spend less time designing and building it. Which makes housing worse, which people want to talk about. And so on.

I have one suggestion for Rep. Alston and Sen. Woodard to solve this problem: Treat the legislative bills as the Program phase, and, if they pass, go straight to the Design phase.

Short-circuit the groundhog.

Immediately after passage, start drawing site plans. Show the decision-makers and the teachers what these homes can look like. Because then, and only then, can we have a productive conversation with teachers about housing teachers.

If we put the cart in front of the horse, as Durham historically does, then that cart ain't going up the hill. Design is iterative. In my experience, engagement is largely fruitless until AFTER there is a design. That is because design is iterative, and engagement (in Durham) rarely has anything to do with a design. Design first. Then, directly engage the development’s proposed residents. Adjust. Improve. Design again. Engage the residents again.

Using terms of professional project management science, good design is iterative, not predictive. Public entities get this wrong always.

Lastly, should Durham be blessed with the opportunity to build housing on public school lands, it will be critical to subscribe to the principles of incrementalism. Why? Because the nefariousness of central planning can only operate at scale. Robert Moses could only execute when he had the power to take out entire ethnic neighborhoods and exclusive rights to billions in parks and toll monies. He had no ability to build incrementally or obstruct the many incremental builders that have always constructed the spirit of New York City. Not only is incrementalism necessary to build great places, but it is also the antidote to those willing to build bad places in a desperate attempt to prove their ideology true.

Incrementalism matters.

In my world, you walk before you run. When grandiose actors seek to take over a process and run before you walk, the results are disastrous. There is a sad history of this with public housing in America.

As housing (particularly social housing) is politicized, critical focal points shift from qualitative community building to a strictly quantitative number of units (as happened with many Great Society projects). Design dollars can be shifted to unproductive (or counterproductive) engagement. Money dedicated to a communal park can be reallocated to (nice but poorly allocated) PV panels and EV batteries. When people with no tacit skills take over a project that requires tacit skills, good projects go wrong. Invariably.

To suceed, everything must be laser-beamed on low-cost housing for low-income citizens. Period.

If affordable housing is the goal, then all other priorities must be shelved. Building unprecedented housing requires an unprecedented focus. To succeed, everything must be laser-beamed on low-cost housing for low-income citizens. Period.

Everything else (defunding police, minimum wage, job training, etc.) should be identified as a red herring and a distraction to this goal. Project leaders must filter for noise. And that requires a gatekeeper with uncommon fortitude to protect the project from people with less than sincere intent. Because in any progressive city, they will come.

Only after that gatekeeping is established could Durham build some inspiring small-scale developments. The city can absolutely do this. But incrementalism is the way. It should start small and then grow. It should prove it can execute and then scale. The foundation comes before the house. In my view, there are no shortcuts here.

CONCLUSION

All in all, HB 1067 is an exciting and clearly needed bill. Cities, counties, and states have a plethora of surplus land, all with a zero-dollar basis. In development terms, it's "free dirt". If affordable housing is the goal, there is no better starting point.

Chuck Marhon of Strong Towns believes that we should treat public assets as if they are stock shares of the citizenry. If the asset is productive, it will be developed with schools, parks, or housing, where it will exhibit a clear quality of life return on investment. If it lies fallow and costs us money while offering nothing, then it is the equivalent of stuffing cash under the mattress. It's not adding any value, and in a growing economy, it's technically losing value. In other words, it is fiscally prudent for cities to develop their lands.

Keep an eye on Rep. Alston's (and Woodard's) bill. This is the first step in the process. Counties deserve to reestablish the right to develop their lands. It's not clear if or when that will happen, but it is clear that re-legalization is always the first step. The real work starts the moment the rights are re-established. We will know Durham is serious about teacher housing when dozens of site plans are on the table, proving how serious it is.