North Carolina's Forthcoming Insurance Shock

Who buys flood insurance 2500' above sea level?

ASHEVILLE, NC | A tropical hurricane hitting the mountains has brought into sharp relief that disaster recovery is about community, including barn raisings and the development of anti-fragility. Helene delivered unprecedented devastation, including loss of life and property damage never seen in Appalachia. In this wake of human despair, a looming sucker punch is coiling: very few of the thousands of homes damaged by the hurricane had flood insurance. Because of this, most damage is unlikely to be covered, resulting in financial stress that, in many cases, will trigger bankruptcies.

I was in the mountains in the days after the floods. No scene appeared more telling to me than a 30-something father of two young children (let’s call him Bob from Boone) surveying the total loss of his riverbed 1970s ranch home, where the lot was strewn with salvaged car parts, and his 20-year-old minivan was somehow perched on top of his displaced 500-gallon cistern. Bob looked shell-shocked. He had little to start with, and all of it had floated away or been left on the lot, destroyed. It was surreal—“Why is my minivan on top of my cistern?” The scene appeared hopeless. Bob looked helpless.

Much of this pain is personal to me. I love North Carolina—my adoptive home since 1984. North Carolina is humble and straightforward, exuding grace and rootedness in its frugal utilitarianism. Simply put, North Carolina is unconsumed with the image, and it’s right there in the state's motto: Esse quam videri, to be rather than to seem.

There is nothing ostentatious about the state’s housing. In the mountains, this is even truer: it’s just people getting by and living their lives. Until recently, the mountains attracted people who wanted to build their homes outside the reach of the long arm of assimilative governments. It’s a self-made place in terms of citybuilding, and that’s a big part of its charm and appeal.

But North Carolina’s small-scale way of life is existentially threatened by how property insurance works in America.

THE THREAT OF FLOOD EXCLUSIONS

The Wall Street Journal recently ran two articles on this insurance problem (both paywalled).

In The True Cost of Losing Your Home in a Hurricane (After Insurance), the article's subjects were relatively wealthy Florida coast homeowners, which created a unique set of circumstances:

The storm did more than $300,000 in damage to [Scott Townsley’s] Sanibel Island, Fla., home. Insurance covered about half of the cost of the repairs, though it took 12 months of wrangling to get most of the funds. Townsley, a consultant, picked up a few more clients and kept working to help shoulder the cost. Townsley considered himself lucky as some of his neighbors still hadn’t been reimbursed by insurers.

Townsley had insurance and job opportunities to make himself whole, but much of Appalachia has no such failsafe: no flood insurance and no consultant wages. Bob from Boone, however, cannot simply get a few more consultant gigs to get back to par. In terms of expectations and local wages, Florida is more prepared for devastation. Even those who don’t buy flood insurance in Florida, to some degree, accept the risks. Not so in Western North Carolina.

Jean Eaglesham’s article Homeowners Hit by Helene Are In for an Insurance Claim Shock highlights how flood insurance policies have become more restrictive:

“Insurers have become significantly tougher on hurricane claims,” said Rick Tutwiler, a claims adjuster for property owners based in Tampa, Fla. “We’ve moved to an era dominated by exclusions, diminishing coverages, and even harsher policy terms.”

Helene's losses might reach $30b, but insured losses are expected to be one-third of that total. The difference is explained by exclusions; policies no longer cover flooding, and few buy separate flood insurance. According to the WSJ, less than 1% of households in the worst-flooded inland counties have flood coverage.

Contextualizing the problem more specifically to Asheville: Who the hell buys flood insurance for a home that is 2500 feet above sea level?

THE POST-DISASTER EXODUS

Property and financial losses are now forcing people to move. Are we facing a modern-day Grapes of Wrath: a slow diaspora away from inhospitable homes fueled by catastrophic environmental hardship? Where will they go? What can be done to prevent the suffering? How can we keep people in their homes?

The issue is not new to Florida, where many residents are bailing on their Caribbean paradises due to insurance rates and hurricane devastations. Many of these re-migrating Floridians hail from New York and “half-back” to North Carolina. This is ironic because The Great North State is generally considered a “receiving” region for climate change. Helene has cast doubt on that logic.

Floods pose a bigger problem in the mountains of North Carolina, where hurricanes are unexpected, wealth is lower, and practically nobody has flood insurance. Impoverished homeowners and 2nd homeowners alike may suffer because with no flood insurance, someone with an $800,000 mortgage on a $1,000,000 home who is wiped out by Helene now has an $800,000 mortgage coupled with no collateral to back the loan.

IN THE LONG TERM - POLICY CHANGES

I see three long-term solutions:

As we rebuild, we can flood-proof future housing. New Orleans and Charleston often build waterproof first floors, with concrete walls and floors and foamboard insulation. Once labeled by new urbanis t architect Andres Duany as “a house that can take a bath,” these structures can take 8’ of water during a storm, then be pressure-washed and back in service in a week. Lower-lying parts of Asheville, astonishingly, may need to start building Charleston-style housing.

Second, rapid-response housing can be developed, which requires increased manufacturing capacity, inventory of homes in advance of disasters, and regulatory reform. Post Katrina, a cadre of New Urban architects were invited to design an affordable and rapidly deployable “Katrina Cottage”. Marianne Cusato got the most press for her work on these. Still, they are charming-looking trailers that can serve the cause of emergency needs but also become permanent long-term solutions for many affected parcels. Why couldn’t FEMA have 1,000 cottages ready to go each hurricane season? At $100,000 per, that would be $100,000,000 of inventory, which could also be sold for nonemergency purposes to help fund the program (I would suggest they underwrite and outsource to a private manufacturer).

Lastly, another solution is the acceptance of risk. To fully floodproof Asheville might cost trillions. Is it more important to a) plan for a 1,000-year event or b) build affordable housing? In Asheville, you can probably only chase one. We must deal with benefits and costs simultaneously and understand those costs relative to other needs. Acceptance may mean becoming comfortable with trauma on a relatively regular basis.

These events will continue to happen. The regulatory disparity between blue New England and California versus the pro-housing and pro-business South means that population growth occurs disproportionally in higher-risk regions. Whether climate is the problem here or not, we know that more people will be in harm's way, making harm more prevalent and more expensive. In the long term, we must find better ways to make buildings more resilient to destruction.

IN THE SHORT TERM - COMMUNITY

The short-term need is charity. Citizens in western North Carolina need money, temporary places to live, and places to put their kids in school. After the immediate needs of safety and shelter are addressed, the clean-up begins. I am pleased to see that it already has.

Disaster recovery is much like a barn raising—community members come together to accomplish a utilitarian task for someone else, with no expectation of anything in return. But barn raisings are about much more than raising barns—they are social events that bond citizens, forge friendships, and strengthen communities during times of stress.

While there might not be any actual barns to raise on the banks of the French Broad, there is plenty to do. If half of Asheville's 95,000 citizens spend the next twenty Sundays cleaning debris, replanting gardens, and fixing homes, then Asheville will be fine.

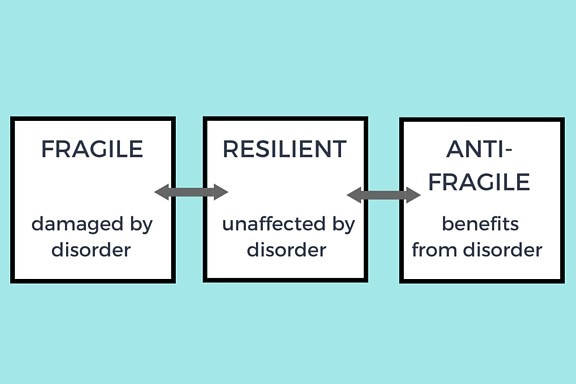

For all the negatives we can cite about disaster recovery, it is during times of trauma that the community shows itself. Helene is now an exercise in how to make a region Antifragile (see Nasim Nicholas Taleb’s book by the same name). In this book, Taleb asks what word is the opposite of fragile? Most people respond with “resilient.” While resilience means surviving under stress, antifragile means becoming stronger because of it.

Instead of asking, “How do we recover?” Asheville and all the victims of Helene can be asking “How do we come back better?”

Because when a community is put under stress, that’s precisely when it shows how strong it is.

This is really well written. Insurance across America is tightening - even in the less weather riskier markets. It is now a “deal killer” !