My Thoughts on CarolinaForward’s Housing Plan

There’s good stuff in here, and this is an incredible opportunity for Democrats to lead on housing.

CarolinaForward released an exciting policy brief entitled "The Middle-Class Housing Plan" this month. They outlined three primary motives:

North Carolina's housing crisis is fundamentally about too little housing being built.

The Middle-Class Housing Plan for North Carolina is a strategy to increase the state's housing supply.

It's time for the state to act.

On most of this issue, CarolinaForward's team is spot on. The rising cost of housing is the leading stressor in life, spilling over into other areas ranging from the environment to mental health. And they do a great job at recognizing the shortcomings of housing policy, particularly an overmeddling by local governments in housing that violates the Hippocratic Oath: "First do no harm."

Too often, politicians approach housing with pure grandiosity, demanding we as a society do things we don't know how to do. The result is a radical decline in the quantity and quality of housing and a collapse of their primary subject market- affordable housing. So, the plan is wise to keep such leaders from tinkering.

Anyone who reads me knows that I am skeptical that governments can build housing well or create housing plans that do more good than harm. But I do think CarolinaForward's strategy is interesting as it seeks to acknowledge these natural shortcomings of cities by 1) focusing on 3rd-party-underwritten gap funding to catalyze desirable projects that do not pencil today, and then 2) quote-unquote "get out of the way." It's a market solution to a policy-created problem.

One critique of note: CarolinaForward suggests that "...Missing Middle housing - townhouses, duplexes, quadplexes and so forth- are often the least financially viable projects to build". I do not agree that this assertion is inherently true. While this might be technically correct, it misses the forest for the trees. Missing Middle is only less viable because it is (generally) illegal. That saddles any project with an expensive, unpredictable, politicized approval process that cannot reasonably be quantified or assured. If the form is legalized (more technically "relegalized"), it is not less financially viable and, in many cases, much more feasible.

So, the issue here is, first and foremost, legality. Legality precedes financial viability.

We as citizens have the right to build this stuff reestablished before we can reasonably determine whether it will be more viable or not.

Consider this example:

In many ways, we don't know if urban townhomes are more viable than urban McMansions. Why? We don't have any precedent because so few people have built urban townhomes recently. We don't have case studies to look back upon. There are few comps on Zillow.

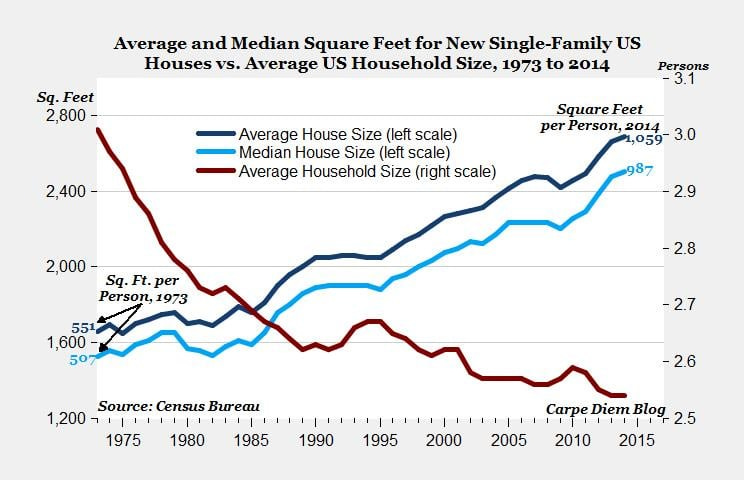

We had a similar cycle in Durham when "small lot homes" were relegalized in 2019. Staff wondered, "Will anybody build 1200 sf homes when the national average for new homes is more than twice that size (closer to 2800 sf) now?".

But the market figured it out, and now, four years later, it appears more small lot homes are being built in urban Durham than traditional lot housing. This is relevant because small lot homes are a Missing Middle type. Here, the market proved that smaller, more affordable homes are 1) viable and 2), in many cases, more viable than the McMansion alternative.

How does an owner decide on Missing Middle housing?

More and more, as housing choice is reestablished, property owners have options for what they can do with their property. Today, more than any time in a century, that requires a pros-and-cons analysis of various possibilities. Missing Middle has clear benefits and costs.

On the upside, Missing Middle housing allows for more homes on a fixed amount of dirt, lowering land costs per unit, the primary malleable variable for achieving lower-cost housing. Missing Middle is more walkable, community-oriented, and can deliver more overall units. It's easier to include community amenities through urban density.

On the downsize, these forms are less precedented, still often illegal, and have fewer comparables for appraisers and lenders to lean on. That makes the delivery cycle less predictable.

It is a strange duality: Missing Middle is simultaneously less risky and more risky to develop.

In this light, CarolinaForward created a unique 3-fold plan to underwrite these markets:

Provide below-market-rate debt for qualifying housing (4% vs. typical market closer to 7-8% now)

Ensure that projects meet a minimum density of 10 units/acre and deliver rent that does not exceed HUD-listed "Market Rent" (bonus for 80% AMI).

Allow projects to override certain permitting restrictions with appropriate zoning and connections to utilities. Critically, "appropriate zoning" is loosely applied to facilitate the state override. And, like California, the state pre-emptive language predicts and preempts anti-housing advocates' typical tools for blocking housing, including technocracy, delays, discretionary reviews, or mismatched proffer requirements.

Big picture?

CarolinaForward's proposal is a good program and the kind of policy we will see more and more of over the next decade. In spirit, it's similar to California's "Builder's Remedy" and North Carolina's proposed SB317, providing entitlement bypass in exchange for 20% of the lots being reserved for workforce housing.

I could not state this more emphatically: These state bills are the specific result of cities failing to act on housing and failing to perform their core duty to facilitate land use that keeps their city affordable and accessible to all. As California's local obstruction industry shows, this can only go on for so long before adults step into the room and take over. While some NC cities have been leaders in reform, most cities still need to do this difficult work. So Raleigh is getting more involved, and assuming cities hold their habits, North Carolina's State Legislature is just getting started.

States will step in. That's inevitable. In California, those preemptions are largely led by Democrats. Preemption is still largely bipartisan in the South, with Democrats like Durham's Vernetta Alston drafting statewide ADU bills and Republicans across the aisle leading on things like building code reform.

I've said it before and will repeat it: The Democratic Party's path to relevancy in North Carolina goes through housing. In this light, Carolina Forward's proposal is excellent. It is explicitly pro-housing and pro-Missing Middle housing. Those are both politically popular items. And it would be suitable flags for the blue team to plant.