I was on the StrongTowns Podcast | Transcript #2

Is Affordable Housing Possible Under Current Zoning Laws?

PART 2: Faith-Based Housing, Affordable Housing & Entitlement Hell

Here on the StrongTowns’ national podcast, I discuss my background, how cities are positioning themselves as national leaders in housing, and the transformative potentiality of incrementalism.

Full Podcast Here | For part 1, click here

Abby Newsham, moderator:

It's ironic that faith-based housing was something that had to be addressed. I hadn't thought about that before because, typically, religious institutions have quite a bit of leniency in zoning codes for religious practice, but the housing practice or home building is a little bit different. Although it makes a lot of sense for a religious organization or nonprofit that isn't necessarily building as a commodity or to make profit to be a builder of housing and to contribute to the overall market in that way.

Aaron Lubeck:

It's been amazing. Thomas Dougherty wrote The American Alley, as is was one of the great young architects in New Urbanism. He was brought down to Durham to lead a charrette in which multiple churches participated. We locally fundraised for it, interests at Duke Divinity helped pay for it, Self-Help, which is a nonprofit bank, also helped underwrite it.

Then, we had four local architects donate their time to draw site plans based upon this proposed code for actual churches with actual sites.

And it was just a fantastic event, really bootstrapped, just to explore “what could this be?”.

We were really amazed because there's 550 religious parcels in Durham County, about two and a quarter square miles of land. My suspicion was that if you talk to churches about whether they're interested in building housing, I don't know. Maybe 20% or 30% might be interested. And I'm pretty good at filtering tire kickers.

But pretty much everybody we talked to was like, "Absolutely. We talk about that. We're interested in affordable housing. We want to give back. We have this mission. We know this is an issue in Durham. We want to be part of the solution."

It was overwhelming how many people were interested in it.

The other thing that was super interesting is that what churches think of when they think of affordable housing is really skewed.

There's the belief in America that affordable housing has to be ugly. It's ingrained in us now.

A couple of the churches that had gone further down this line already had this imagining in their head, like a garden apartment with a vast surface parking lot, because that's what LIHTC affordable housing projects are. They’re ugly.

They didn't know that you could do something different. Or better.

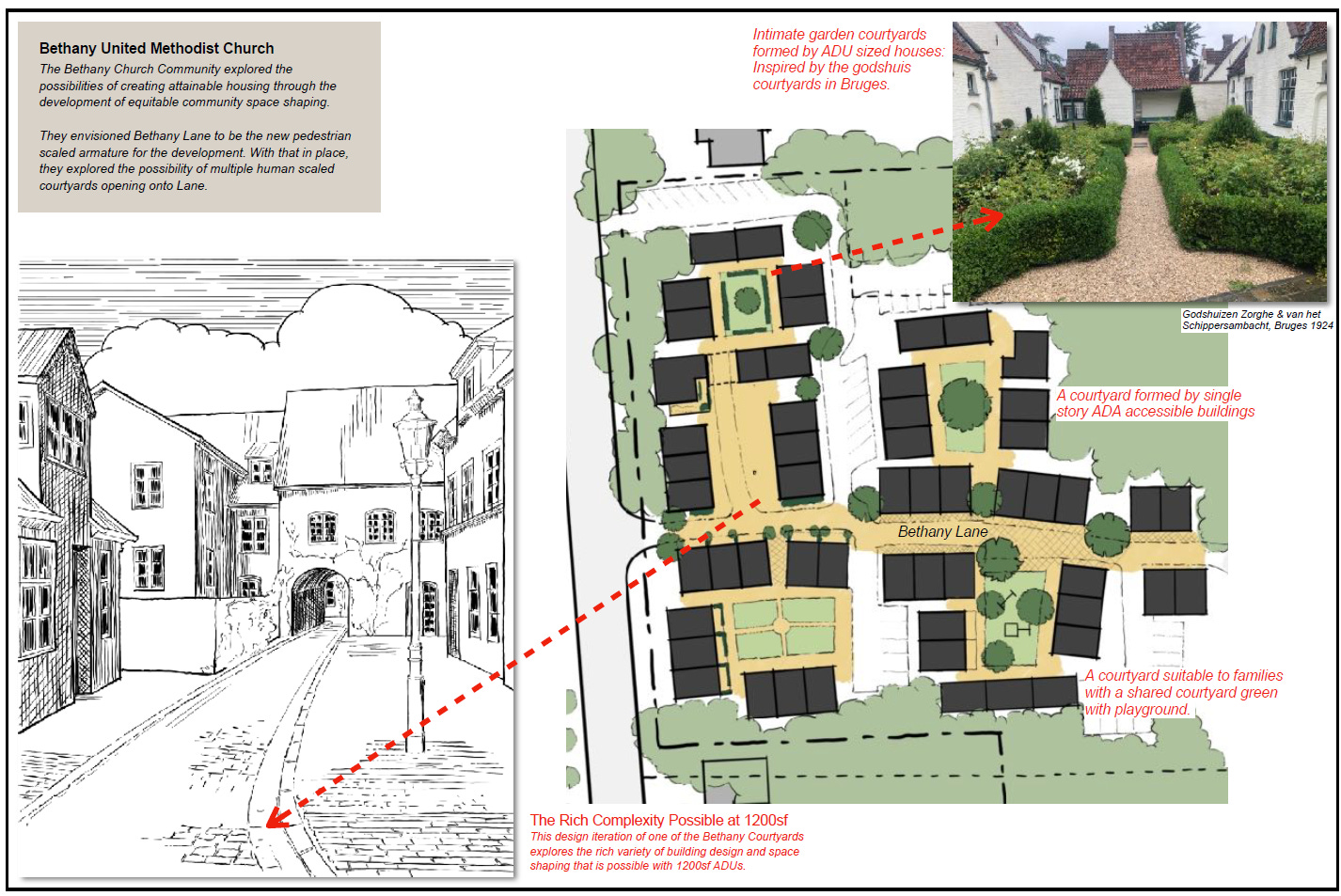

Thomas Dougherty, who designed a site for a Methodist church here, designed village housing that looked like something out of Bruges, Belgium.

It had no huge surface parking lot. It had less runoff. It had more green space and more community space.

It absolutely would be one of the coolest developments in Durham, and would probably cost less to build than the crappy garden apartment.

It was mind-blowing. I mean what came out of the charrette was truly mind-blowing.

And now we’ve had faith-based leaders from across the country saying, “We're watching Durham because this has implications beyond Durham.” This could be something that really radically helps the affordable housing issues across the country, very quickly.

Abby Newsham, moderator:

When people often think about affordable housing, you say LIHTC, but I think about “capital A” institutional affordable housing. It's like a piece of the puzzle, but we can't just have institutional housing and then luxury market rate housing that you need attorneys and a bunch of specialists to get through the process in order to build. And what I think the code amendments that you're proposing are doing is effectively enabling more incremental development and more starter homes. I mean small lot housing is a big opportunity for starter homes, just to build smaller format housing. And you obviously need to build a building culture that is able to do that work. But it's kind of occurred to me that we have organizations that really focus on small business development, building capacity, addressing regulatory barriers for small businesses, but small developers are a type of entrepreneur that I think doesn't really get a lot of focus and is so impactful to the housing market and to just the overall ability for people to thrive in our country.

Aaron Lubeck:

You're totally correct. And so I think the way you described it was beautiful. We were talking about small homes and small lots, but we should be talking about small builders.

And so much of my advocacy work is assisting that class. I've been that small builder when I started in this industry, and I didn't have a pot to piss in. I did not grow up wealthy. And I know this is a capital-intensive industry, but it is possible to enter without being a trust fund kid.

We also know about the writing on the wall for cities that got this wrong. If you live in San Francisco, love San Francisco, and want to build in San Francisco, you can’t. You can't start if you're just a young kid with hustle, and build a duplex. And that's a really dangerous place to be.

And so, we need to defend and create paths for young kids coming out of high school and micro jobs, such as blue-collar training. Where can they go build? These are real questions we should ask.

We've got a great construction and construction and management program at Southern High School. We've got Durham Tech construction training. NC Central just started a real estate training program. Duke students just started an Urban Studies Initiative program. The kids want to do it, they’re simply deprived of the opportunity.

And so here's the fundamental questions:

· Where does a 22-year-old who falls in love with Durham and wants to build Durham go?

· What's their path?

· Where are the lots they can build on?

· How hard is it for them to build?

And if you run into roadblocks there, it's a policy question. And it's not unsolvable. But we need to defend that right of entry, otherwise, you start removing rungs at the bottom of the ladder, and they're much easier to keep than to put back.

Abby Newsham, moderator:

Well, and then the outcomes that you get are people broadly lamenting - why are we just getting luxury large scale development? And it's because the ability to do modest or incremental development has been removed from the equation. You have to consider the risk, the barrier to entry, and whether it is a viable path for people who are not really trying to get into corporate real estate development, but love old buildings and want to renovate buildings or love their neighborhood, and they'd love to build a duplex or build something small, do the next small iterative thing.

And I think you would think that from a public engagement perspective or acceptance perspective that people would be a lot more accepting of that approach. But as you're seeing, you still have pushback even for more iterative change. And we see it too.

We work on a lot of zoning issues, especially out in the Mountain West and this region of the country. And I mean, even iterative change in some places is unacceptable to a handful of people. Do you think that's something that has become more intense post-COVID, or has that always been around?

Aaron Lubeck:

So for me, COVID has not had something to do with it. But I would say that it's gotten worse over time and some of it is intentional, most of it is not. It's sort of the nature of bureaucracy that powers always expand. And then every city has a handful of malicious people who are leveraging these realities to make it worse, to prevent housing and amass power.

So that happens first at planning with zoning, that it just sort of doesn't work, either intentionally or not. Secondly, there is a body of the planning and political professions, not a huge faction but very relevant, that defends “pre-textural zoning”; that's essentially zoning that intentionally does not work.

It’s designed so an applicant has to beg for special permissions, where they get you in front of a public square where they can squeeze for a variety of proffers or whatever their personal interest is.

Proceduralism an issue where in progressive cities entitlements intentionally take forever: you hear the horror stories of 10 years in San Francisco. In Durham, they've gone from three months to 18 months. Engineers say the average entitlement now costs $150,000.

I mean, so think about this from a small builder perspective, who's transferring from the teaching world to building, this cost isn't just a line-item expense in your project. This isn't $150,000 that you'll get back one day when you build the thing. This is $150,000 on a craps table; you might not get it back.

You can't tell if you're going to run into a planning commissioner or a city counselor who had a bad day or who is going to grandstand on whatever their issue is and squeeze you or kill your project because of some unrelated issue that it has nothing to do with you or your project.

It's a risk. There are real thresholds at which the small builder will not participate. And in progressive cities, more and more builders won't participate because it's too much risk to participate. And that's a really dangerous place to be.

Abby Newsham, moderator:

The level of risk that goes into just getting approval to do a project. I think that's why Monty always says, “don't do a first project that has any changes to zoning.” He's allergic to zoning issues. But I mean for a good reason because you can get caught up in zoning change debates that could go any way, and you might invest $10,000, $20,000 in that process and get denied, and now you can't do your project.

Aaron Lubeck:

And it's one of these things that we see, it's really sad. It was one of the motivations for the SCAD amendment because we hear more-and-more from friends that they're looking at doing a compromised project that either has bad setbacks that force trees to be removed or extra runoff that has to be created because of parking mandates, or they say “I'd love to do a garden that's shared”; but they can't, because they have to park all the cars off the street.

All this dumb stuff that, if anybody looked at the site plan, would be like, “Yeah, that's stupid. We shouldn't do that.”

But this is an actual decision-making process that I think the planning industry and politicians don't understand: the builder has to decide, “Is this worth the brain damage to go get a variance or a rezoning, or the text amendment or whatever?”

Return on Brain Damage is a calculus only practitioners can understand.

And because the process is long, and it's expensive, and planning is more and more political, increasingly the decision is that “I'm going to build something that's not ideal, that I know is less than what I want to do, and could be better, because it's not worth the brain damage to go get the special permission.”

And again, that's harmful. It’s harmful to everyone. And a good chunk of, actually the majority of, SCAD is technical cleanup to avoid those undesirable ends.

Again, something as simple as getting rid of parking mandates will turn pocket neighborhoods that are currently required to be a parking lot into a beautiful garden. And that entitlment needs to be preserved, by-right, because if the small practitioner has to go beg permission for it, it simply is not going to happen.

Abby Newsham, moderator:

The ability to basically get a building permit for projects that are iterative and additive to a neighborhood I think is the key here. However, I think that is where you get a lot of the pushback. People talk about by-right development and there are people who want to review every little change to the neighborhood, and it's a very fine balance for communicating and having conversations about, as a citizen, what level of control should you really have over your neighbor? We're obviously not assessing the plants that people plant in their front yard, or there are all these things, I guess, unless you're in a homeowner's association, maybe. But every place has a different culture around how much control we should have over neighbor's property based on your stake in the neighborhood because it's typically homeowners that are debating these things.

I mean, can you talk a little bit about that and how you communicate around these issues of wanting to have standards that help to manage potentially bad impacts of development while also streamlining development so that things can happen?

Aaron Lubeck:

Yeah. And I think every district is different, and we know, I try to contextualize this knowing that cities are different than suburbs. Fundamentally, most of the problems that we can identify in the CNU, Strong Town, Southern Urbanism world stem from the fact that we've suburbanized our cities. We've taken concepts that were emphatically suburban - climax condition, monolithic use, parking standards, sprawl, the elimination of poor people, the elimination of apartments - and retrofitted them onto a foreign being, which were cities.

So if cities were just allowed to be cities, which are the antithesis of suburbia, they’re flexible, they're organic, they're entrepreneurial, they're job markets, they're creative and incremental -then cities would be able to evolve without all of this rigamarole.

And honestly, I don't think we'd have the affordable housing crisis that we have because cities have always historically for 2000 years provided when they needed to. For me you're right, especially in the South, honestly a lot of our cities are suburban. A city like Raleigh, which is a pretty amazing place that has done great things, 80% of that city is suburban in form, which makes reform really difficult.

I think finding the path to create relief valves is critical. Our downtown was basically unbuildable for 30 years. We fixed that 20 years ago. It boomed. The more we can build downtown, the more we relieve pressure from the neighborhoods. Neighborhoods do have a right to be reasonably protected. You don't want a 10-story apartment building next to your house, and that's understandable.

The issue is when everything is so tightly frozen, when opportunities to build come up, they're almost like the pressure goes to build unaffordable mediocrity.

We know that one of the things in SCAD is restoring is neighborhood commercial rights. We've got about nine neighborhood commercial districts in Durham that are all functionally dead; well, not all dead, but basically not thriving because it's impossible to build a new building there.

The most basic and basic urban forms, like a one-story commercial building with a diner connected, simple as can be, have been functionally banned for 50 years. So we need these relief valves to relieve pressure and retain our walkable urban neighborhoods.

Abby Newsham, moderator:

So 50 years plus of regulating and building our way into the current condition. I mean zoning is obviously not going to change things overnight. It'll probably take 50 plus years to change our way out of this, even when regulatory standards change. I think a big part of that is probably looking at the building culture and people who are doing this work once the work can be done. How is that in Durham? Is there a strong culture of smaller-scale entrepreneurial builders that will leverage this kind of regulatory change?

Aaron Lubeck:

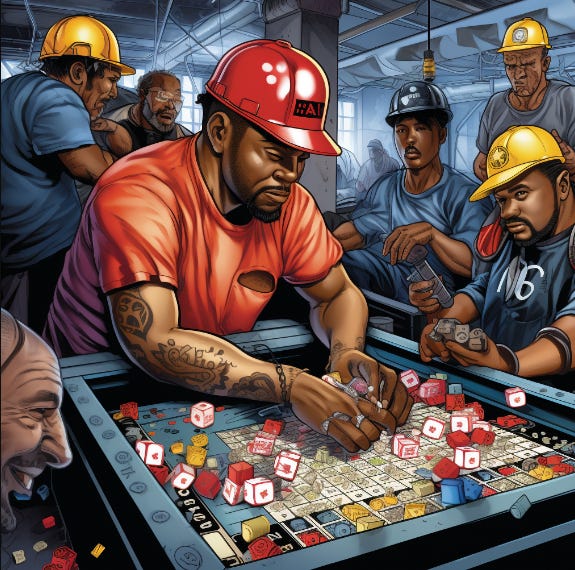

Yeah, there are. And it's interesting because we have a Builder's Guild that's small and sort of informal. And it's got a combination of some really successful people who've done this for 20 or 30 years combined with some young folks who are just getting involved.

A good friend of mine, Tiffany Elder, runs a Black development group, it's actually a Black real estate group which includes affordable housing builders, and realtors. And it's great because it is like people who've done it for a long time engaged with the 20-somethings who just have fire in their eyes. They're just like, "I want to build the city. Tell me what to do, tell me what to do, tell me what to do." You can see that people are going places. That needs to be cultivated.

And a lot of that obviously is regulatory. If you can't build, you're not going to pretend you're a builder for very long. You're going to teach or do something else. So the first thing a city needs to do when it finds itself in a hole is to stop digging.

But beyond that, I do think that there's a boom coming in that once you can get past these silly fights of whether you have a right to build housing or not, only then do you create this space where we can actually start talking about building beautiful houses and beautiful projects and so forth.

Because we look at our most progressive cities, which correlate with the sort of worst zoning and restrictive ability to do anything, and a lot of them have really bad architecture. I mean, especially over the last 50 years. Some of the worst architecture is in California.

And I ask people around Durham, I'm like, "What's the last project that inspired you?" And people ponder forever and then they're like, "Well, American Tobacco Campus," which is a major adaptive use tobacco factory, and it's like that was 20 years ago. I mean it's crazy, in a creative class town that is booming, that we're not building anything that's inspiring in a quarter-century? That is just not acceptable.

And so again, really people won't believe this, but a huge chunk of it is that people are so exhausted having arguments over silly things that there's only so many hours in the day and if you waste time there, you have less time to design beautifully. So we are getting there, but the right reform is a prerequisite to incredible places, there's no question about that.

Abby Newsham, moderator:

Yeah, absolutely. You're so right about the architecture issue. It's pretty unfortunate and pretty brutal out there.

Aaron Lubeck:

I call it the “California Effect” because it's when the market gets so tight when there's such a low days-on-market, and there's no elasticity, the builders are effectively saying, "Whatever I build, you're going to buy. Why would I try to do something better? Because it’s so tight, I'm going to build something, and you're going to buy it." So there's something to be said for finding equilibrium.

A lot of the anti-housing groups will complain, sincerely or not, about that bad architecture, but their advocacy - to prevent elasticity and prevent supply - absolutely has a downward pressure on the quality of architecture. No doubt about it.

All you have to do is look at the kind of housing they built in California that led this movement for the last 50 years and nearly all of the housing that's been built is ugly, uninspired sprawl.

Abby Newsham, moderator:

And even whether or not you're going to get a design architect involved on a project that can effectively build a nice building or if it's just more of a copy paste approach, which is unfortunate. It'd be great if that would change one day.

Aaron Lubeck:

It comes with the rights, but I do think it's coming.

____

Part 3, the epilouge, coming soon Full Podcast Here