A Requiem for The River Arts District

North Carolina's flagship for authentic incrementalism is gone.

tl/dr

No North Carolina district represented human-scaled local development better than Asheville’s River Arts District.

Like California in the 1960s, it was a land’s-end representation of dream-chasing and micro-community formation.

River Arts is more than just physical buildings. It is one of the best presentations of Southern ingenuity for the state. It has to be re-birthed and re-built.

1 ASHEVILLE

If you identified as an artist and sought to surround yourself with like kind, there was only one place in North Carolina to go: The River Arts District.

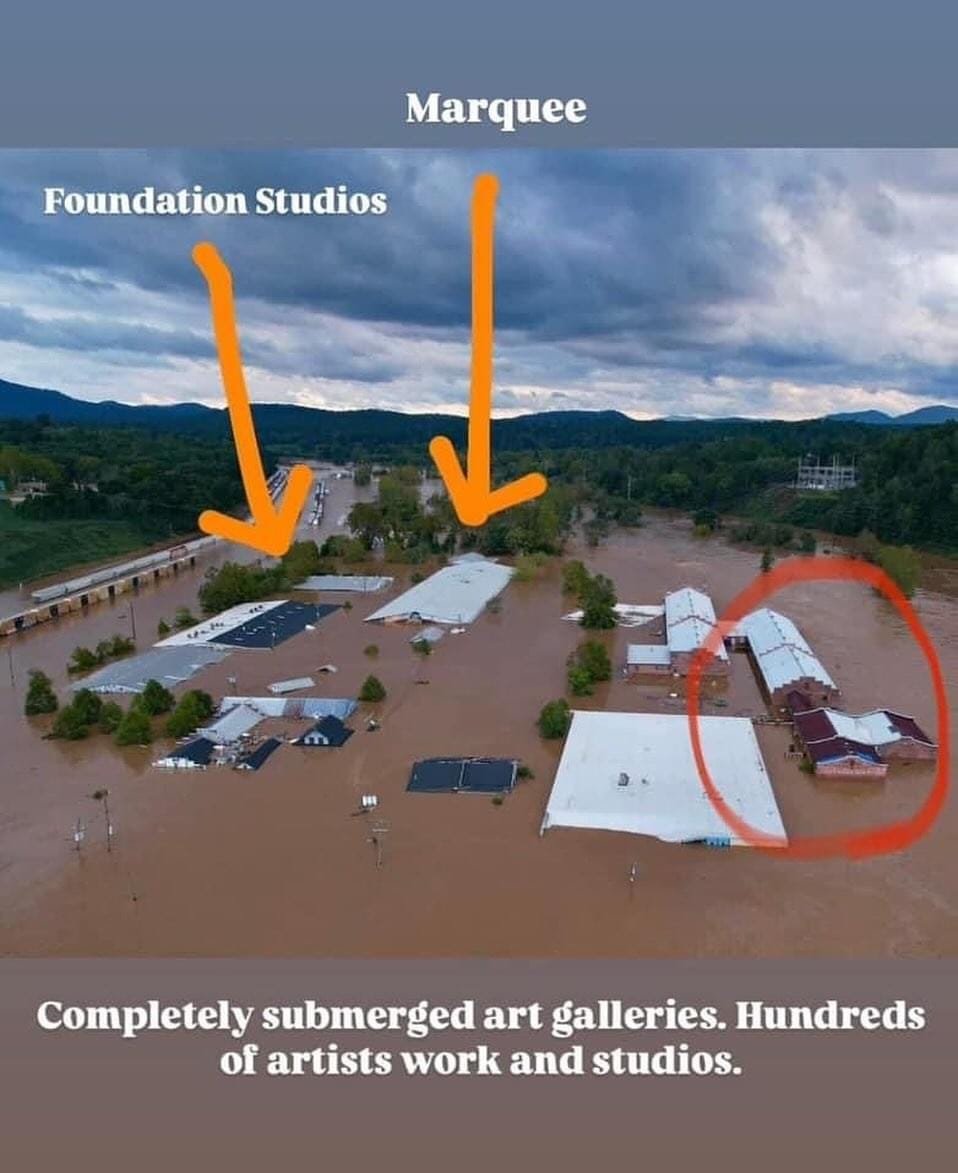

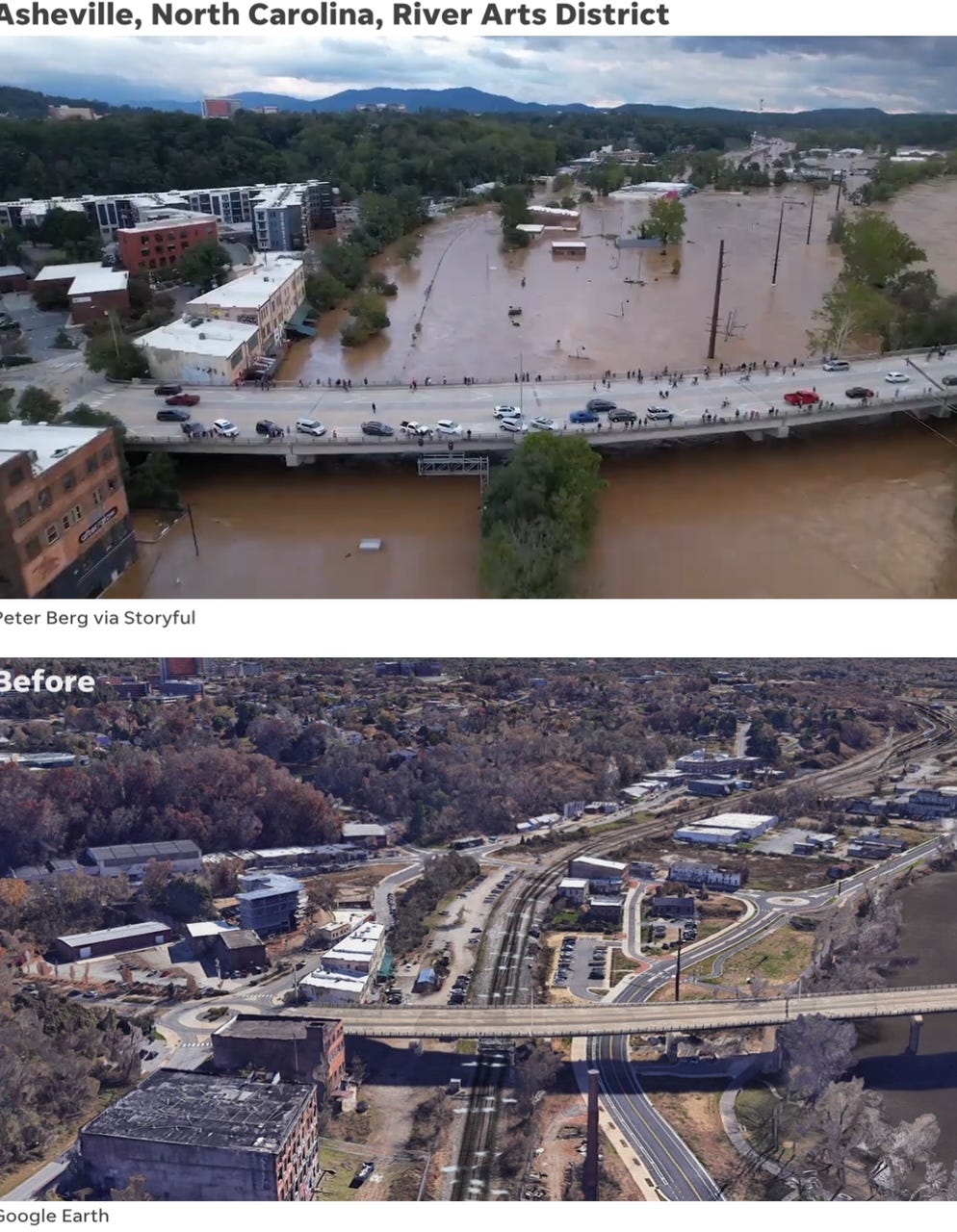

I was in the mountains on September 27th, 2024, immediately after Hurricane Helene hit. Few areas were hit harder than River Arts. Much of the district was under 25’ of water, with the lowest terraces completely wiped out. Despite what was described as a 500-year flood, it appears that the historic row buildings—which anchor the district—survived, but with significant water damage. I pray that they are salvageable, as they are the DNA from which any hope of restoration will flow.

One of the reasons River Arts is worth studying is the third-fiddle role the district played in Asheville. It’s lesser known than the city’s two main attractions: the grand Biltmore Estate, marked with wineries and baron-worthy architecture, and the lively downtown, filled with James Beard Award-winning restaurants and world-class breweries. The River Arts District represented an organic alternative localism—undercapitalized, scrappy, and alive—all things I persistently advocate for under the broad-brush brand of incrementalism.

What is incrementalism, and why does it matter?

Despite decades of advocacy from Jane Jacobs and groups like New Urbanists, as well as the Incremental Development Alliance, incrementalism is still largely misunderstood.

Most people think of incrementalism as small buildings and small businesses—built locally, one at a time, without scale. They are messy. They generally have undercapitalized builders, are often developed by non-professionals, and are subject to all sorts of crazy stories of partnership stress, entitlement snafus, loan shortfalls, etc.

Incrementalism is also where 100% of a city’s placemaking happens.

The places that matter—the places that people identify with and think of as their own, the places where people do first dates and fall in love—they’re almost exclusively incremental. You don’t take a date to a corporate Chili’s; you take them to Katie Button’s Curate.

Incrementalism is largely synonymous with localism. Wall Street has never built a James Beard Award winning-restaurant. And they never will. They can’t because, at Wall Street’s scale of financialization, risk aversion is the name of the game, pushing all development into an unambitious, predictable, mushy, mediocre middle.

The antithesis to this financialized mediocrity is localism. The one and only cure for run-away machine-like corporatism is a fierce and unbending commitment to localism.

Few cities practice localism better than Asheville, and few places in Asheville practiced incrementalism better than the River Arts District. In a sense, the River Arts was North Carolina’s micro version of the Californian Dream which, for a time, was the climax condition of the American Dream.

2 THE HAPPINESS EXPLOSION

That dream is best defined by what writer Tom Wolfe described as The Happiness Explosion. In that piece, Wolfe equates quality of life with small, hyper-focused communities.

Wolfe identifies Los Angeles as the apex of these status groups, which we might today call an identity movement:

“Southern California, I found, was a veritable paradise of statuspheres; Beyond the customizers and drag racers, there were surfers, cruisers, teenyboppers, beboppers, strippers, bikers, beats, heads, and, of course, hippies. Each sphere started off self-contained but increasingly encroached on, and influenced, the wider world.”

In other words, no matter what weird thing you were into, no matter how out there you might be, in California, you could find your people. You could find your community. And you could belong. And, because others were doing the same, you could easily experience adjacent micro-communities, cross-pollinate ideas, and bring joy, understanding, and meaning to a broader humanity.

L.A.’s hippie surfers and Asheville’s micro-brewing metal artists are both by-products of Wolfe’s definition of community development.

I don’t know of any city in the South that captured The Happiness Explosion thesis better than Asheville. If you were a fancy wine drinker and horseback rider, Asheville had your people. If you were a mountain-biking beer snob, Asheville had your people. If you were star-struck by celebrity chefs, Asheville had your people. If you were an artist, Asheville had your people.

If you were an artist, Asheville had your people.

None of these communities were as incremental or geographically defined as the River Arts District. In many ways, it was the beating heart of the intentional community movement in the South, and one of the best 21st-century examples in the country.

3 WHY WE MUST REBUILD

In my design work, I constantly work with clients who want to build better, including micro-communities. At the extremes, these ambitious developments are an exercise in both the physical form (which we call “the hardware”) and community programming (which we call “the software”).

Hardware-wise, the River Arts was anchored by a row of historic buildings but also had lots of unremarkable infill around it. And it is adjacent to a loud and imposing interstate. The point is that great places are often developed on flawed corridors, and class-A architecture is an unnecessary prerequisite for building high-quality communities.

At the end of the day, community is a software problem- it’s about event programming, brand, pride, vision, member empowerment, and self-actualization.

The term “software” then, in this sense, is misleading because it implies you can control these things quantitatively. Communities, though, are inherently organic, idiosyncratic, and unpredictable. I have many friends (primarily Bay Area-based) who still believe you can literally “program” communities with self-learning software algorithms that can create human connection.

I’ll short any such business.

Placemaking cannot be done via an app. Technology can help, but at the end of the day, placemaking is done over coffee and drinks, and unbending local developers signing non-traditional leases with undercapitalized tenants who Greystar wouldn’t lease to in a million years. There’s no playbook for this game. You can’t learn how to do this at business school.

The River Arts District played this scrappy game better than any other. The community took decades to build, and by all accounts, the District was still growing.

It will be difficult for the River Arts to restore itself. The buildings can be cleaned and repaired, but many businesses are gone. New leaders will need to be identified, and not just any leaders, but the kinds of people who are willing to commit 20, 30, or 40 years to curate a single place. That’s rare.

The 60-year-old artist, who had operated in the district for decades, now faces the decision to fight on or close shop, and no one would blame them for choosing the latter.

Who is willing to do the thankless and exhausting tasks of begging for money and special permissions in an environment where thousands of others in Helene's path will do the same? Do River Arts’ leaders have time for politics? River Arts-style incrementalism is small and agile. Policy and subsidy are inherently big and dumb. The problems and solutions appear to be misaligned.

Much more will be known in the coming months. At the moment, I feel like I am at a funeral.

The loss feels more spiritual than physical. While the sheer scale of the trauma in Appalachia is overwhelming, symbols of community matter because they become the reason to build back, and the reason to fight on. The anchors of any place are civic buildings and civic districts, which serve the existential function of getting people to care enough to fight.

That’s why it is so crucial that the River Arts District build back. For Western North Carolina, and the movement of incrementalism, it’s too important not to.

Aaron, that is a beautiful piece that captures what has proven to be a difficult phenomenon to explain. With hope, Asheville will step up and fight its way back. As devastating as this is for all of the different interests that make Asheville be Asheville, it is the opportunity to build back better. LC Clemons tells a story of two neighboring towns that were hit by devastating tornados and how, in the one that had a strong community, everyone came together immediately to help each other rebuild, while in the other that was really just a sprawl zip code, the people were sitting waiting for someone to come save them. My bet is that Asheville has that community that is already overwhelming the supply train, the system, and even one another with their enthusiastic commitment to make sure that this gets done.

Sadly, the lessons of Katrina suggest our systems won’t let this be rebuilt incrementally. Insurance premiums will rise substantially. Mortgages will have to be refinanced. Codes will require upgrades. All that contributes to the area likely either lying totally fallow or rebuilding without the incremental nature we both adore. Sure hope I’m wrong, but right now we just aren’t wired as a society to do it in a fashion that enables creation of places like this once the formal authorities get involved.